The Texas Navy

Naval History Division

Navy Department

Washington, D.C. 1968

Introduction

The Critical Role of the Sea

The Role of the Texas Navy

1835 - 1838

The Texas Navy 1839 to the End of the Lone Star Republic

Ships

of the Texas Navy

Some signifigant Events Relating to the Texas Navy

INTRODUCTION

In the long course of history seapower has played the controlling role in

most of man's struggles. Because of unique advantages of mobility, ease of

mass transport, speed, surprise, flexibility, concentration, and facility of

change of objective, small forces afloat may often have large results. This was

true indeed in the Lone Star State's wars.

In the long course of history seapower has played the controlling role in

most of man's struggles. Because of unique advantages of mobility, ease of

mass transport, speed, surprise, flexibility, concentration, and facility of

change of objective, small forces afloat may often have large results. This was

true indeed in the Lone Star State's wars.

The first half of the Nineteenth Century brought vast changes to North America. The far-spreading wilderness of the southwest was being colonized by United States citizens. Mexico, inheritor of Spain's possessions, was losing her grip over the northern territory. By various enducements she tried to populate this area with citizens from old Mexico; but in vain. Her citizens refused to migrate into the harsh "uncivilized north." As a last resort Mexico opened Texas to foreign immigration, if the newcomer would swear allegiance to Mexico. Once the gates were opened, however, the flood of immigrants could not be controlled. Ineffective administration and internal strife within the Mexican Government caused discontent among the recent arrivals. The seeds of Texas Independence began to sprout.

Seapower was also in a state of transition. In this period navies were in the early stages of one of the handful of fundamental revolutions that through history have progressively increased the power of navies and their advantage to nations wise enough to be strong at sea. Steam engines, iron hulls, and improved guns were slowly changing naval warfare. Twenty-one short years before Texas declared her independence ( 1836 ) , huge ships-of-the-line recoiled under mighty broadsides at Trafalgar, while but 25 years in the future the shots of Virginia (Merrimac) ricocheted off Monitor.

Good books like General Jim Dan Hill's "The Texas Navy" and Commander Tom H. Wells' "Commodore Moore and the Texas Navy" have interestingly covered the operations of that Navy in the 1830's and 1840's. However, lack of spectacular sea battles, the few ships employed and the notable actions ashore, like San Jacinto and defense of the Alamo, have obscured the importance of seapower in the Texas War of Independence. The Navy was small hut large enough for the task. It lacked superior warships, but steered by resolute men it played a decisive part in Texas' independence.

We were able to develop the following brief account through a fortuitous circumstance. Commander Tom Wells came to the Division for Summer Reserve Training Duty. From his book and his notes he developed a sound, basic manuscript which then received the attention of several others of us to fit it to the Division's general pattern. We owe appreciation to the following (some not now with the Division) for their assistance in the editorial and photographic features of this small but useful booklet: Captain F. Kent Loomis, Cdr. C. F. Johnson, Cdr. V. J. Robison, Dr. Wm. J. Morgan, Henry A. Vadnais, Lt. ( jg) Dick M. Basoco, Lt. ( jg ) Wm. F. Rope, Don R. Martin, James L. Mooney, R. L. Scheina, and Alfred Beck.

Americans should know more about this little understood chapter in our

history. The more they understand the role of the sea in America's past, the

wiser will be their use of its decisive power in the future.

E. M. ELLER.

THE TEXAS NAVY

I. The Critical Role of the Sea

In the 1830's, events of fundamental importance to the United States began to take place in the vast, sparsely populated southwest area that in those years became an independent nation the Lone Star Republic. The United States, after purchasing the Louisiana Territory, grew steadily toward a true insularity, spreading from sea to sea.

Naval power had decided her destiny so far. Within generations, the fleets of the United States would decide that of the world. Texas was destined to play a large part in that drama, but first she would write her own stirring story—in which the sea was similarly decisive.

Small nations, as well as large, may find their existence dependent upon a clear understanding and timely application of seapower. The Republic of Texas owed its precarious life in the decade between 1835 and 1845 to a combination of its own temporary strength at sea and the fortunate action of larger naval powers.

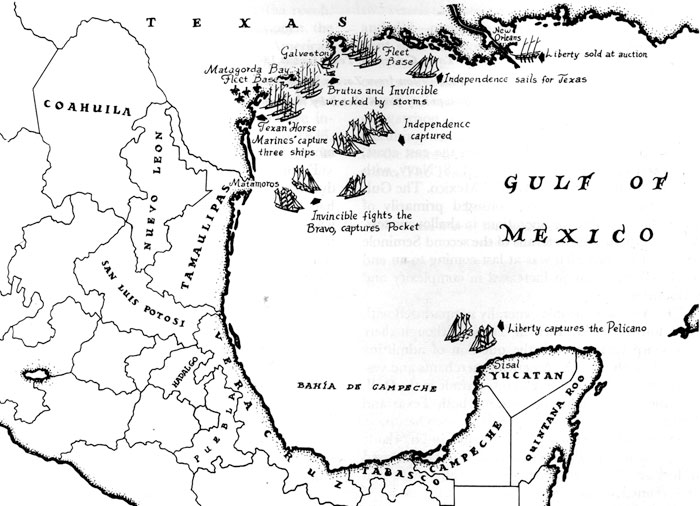

The accompanying chart, part of which is based upon surveys made by the Texas Navy, illustrates the essentially maritime character of affairs both during and after the Texas revolt against Mexico in 1835. The Western Gulf of Mexico is shaped like a giant "C" with New Orleans at one end and the Yucatan Peninsula at the other. In between, from the Tropic of Cancer to the present site of Corpus Christi, sprawled a virtually impenetrable desert, relieved only along the coast by an occasional seaport, such as Matamoros at the mouth of the Rio Grande.

Men could march across the arid region, but neither Texas nor Mexico was ever able to solve the logistic problems inherent in such an operation. In the Mexican War, General Zachary Taylor would encounter the same difficulty of supplying his troops and he, too, would be unable to master these arid reaches. It proved impractical for either Texas or Mexico to sustain an assault on the other by land.

The Texans, who were concentrated in the area between the United States border and the Colorado River along the navigable streams fairly near the coast, turned naturally enough to the sea. New Orleans and Mobile, at the tip of the "C", represented a ready source of men, munitions, and money; and communications with these ports were almost exclusively carried on by sea.

In 1835 about 40 merchant ships, almost all flying the American flag (those emigrating to Texas apparently still felt entitled to the United States citizenship they renounced when they went to the Mexican Territory) , plied between Texas and U.S. ports. For the most part they were small vessels between 80 and 90 tons, but they held the only real hope for supply and reinforcement in the prolonged conflict with Mexico. The large steamship Columbia, for example, carried more than 700 volunteers into Texas on two voyages, a force more than three times the size of that lost at the Alamo and almost as large as the victorious Texas Army at the battle of San Jacinto.

Further south along the coastal "C" were the principal seaports for Mexico's populous highlands — Tampico, Tuxpan, and Vera Cruz, the gateway to Mexico City. The bottom of the "C" was a quagmire of swamps and marshes which prevented effective overland communications with the Province of Yucatan.

Yucatan was the New England of Mexico, the shipbuilding and sailor-producing section of the country. It was here that canoas, 50- to 60-ton vessels which formed the coastal trading and fishing fleet, were built, manned, and operated. The province was so isolated from the rest of the country that it was frequently neglected. Accordingly, it was often in or near a state of rebellion against the national government.

Inside the tip of the Yucatan Peninsula were the Alacaranes and Areas Islands, and outside it the larger islands of Mujeres and Cozumel. All were utilized at some time by the Texas Navy for operations against Mexican vessels.

Once Texas proclaimed its independence, the strategies of the two adversaries at once became clear. Repeatedly, the Texans not only had to prevent a seaborne or sea-supported invasion from the south, but also had to protect their sealanes to New Orleans and Mobile in the east. In performing these twin tasks, they had to inflict unacceptable losses on Mexico so that the latter would recognize her independence.

On the other hand, it was incumbent upon Mexico to project a sizable army into Texas and sustain it there, while at the same time she would have to prevent a mutual defense agreement between Texas and the turbulent, ever rebellious Yucatan. To achieve its aim, Mexico would have to control the sea.

Political and economic strife within Mexico greatly aided the Texas cause, for Mexico was still rent by the chaotic aftermath of its revolution against Spain a decade before. But it was the Mexicans' inability to comprehend and employ seapower that helped the Texans most. The new Republic's foe failed to blockade the Texas coast effectively. And Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna's great overland invasion was blunted and turned back because of inadequate logistic support which, in its own turn, was caused by the timely action of a few warships of the Texas Rangers. Mexico's lack of understanding and appreciation of the meaning and techniques of seapower gave the Texans advantages they sorely needed.

Although Great Britain, France, and at times Spain, all maintained naval forces in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, the only principal seapower in the area was the United States. The American Navy was small in comparison with the fleets of the older nations and in proportion to its large merchant marine, but it did have cruising stations off Brazil, West Africa, in the East Indies, and in the Mediterranean. In addition, scattered units were employed in exploration, such as the Wilkes scientific expedition to the Pacific and Lynch's survey of the River Jordan and Dead Sea area.

The Home Squadron, located on the east coast, composed the main strength of the U.S. Navy, with a small flotilla kept in the Gulf of Mexico. The Gulf Force based at Pensacola, consisted primarily of small ships suitable for operations in shallow waters. Many of them were veterans of the second Seminole War in Florida which was at last coming to an end as the Texas question increased in complexity and seriousness.

The American people generally sympathized with their former countrymen in Texas, although there was sharp division over the question of admitting Texas into the Union. American merchants and vessels conducted a large and lucrative trade in the Gulf, and the bulk of material entering both Texas and Mexico came in these and British merchantmen. Therefore, the questions of contraband and blockade were not simply of academic interest to be discussed in foreign offices during the conflict; they were real and immediate problems involving large sums of money and vast quantities of material.

From the early days of the nation, and particularly during the Napoleonic Wars, freedom of the seas had been an extremely sensitive point with Americans. The country's merchantmen demanded the freedom to sail without hindrance wherever they could load or discharge cargo. And they expected their Navy to protect them.

Other countries had the same concern for their commerce, but none was more solicitous of its rights than the United States, and none could boast of such a spectacular rise in international trade. This zealous care for freedom on the high seas often brought friction — and sometimes crises — but it was an indispensable contributor to the greatness which the nation attained. The naval experiences of the Republic of Texas are a significant part of the transition of the United States from a new and somewhat backward country into a world power of the sea.

II. The Role of the Texas Navy, 1835-1838

Texas revolted against Mexico in the autumn of 1835, but it was not until 2 March 1836 that it formally seceded. The roots of the rebellion were in the differences of race, religion, language, law, and the ideals of government between the Spanish-Indian civilization and the culture of the former citizens of the United States. Yet the immediate causes lay very much in maritime and tariff problems.

A particularly inflamatory incident took place on 1 September 1835 when Texans embarked in the American merchant ship San Felipe and steam tug Laura, engaged the Mexican treasury vessel Correo de Mejico at Brazoria. After wounding her captain, they accused him of piracy when he could not produce his commission and took him and his vessel to New Orleans. The court there delayed the Correo de Mejico, as well as her officers and men, for three months before Mexico secured their release. During this period, the Texas coast remained unpatrolled by Mexico and was wide open for the introduction of men and munitions for the revolt. Without the ships to keep their own coast open the Texans had succeeded in substituting American courts for the seapower they so urgently needed.

The Correo de Mejico incident, however, also greatly aroused Mexican public opinion and was probably a contributing factor to the punitive invasion of Texas by Lopez de Santa Anna in 1836.

The Mexican Navy did have ships available in northern Mexican waters to replace the Correo de Mejico while she was inactive at New Orleans. But the vessels were not used to their best advantage — primarily because of the activity of Texas privateers. By Christmas 1835 the Texas Consultation, a provisional congress, had authorized the issuance of six letters of marque and reprisal. One of the privateers, William Robbins, on 19 December 1835 recaptured the small American schooner Hannah Elizabeth, which had been seized by the Mexicans for having on board two cannons and other contraband for rebellious Texas.

The capture of Hannah Elizabeth, the seizure of Correo de Mejico, and the threat of other losses at sea caused Mexican authorities to commence convoying their ships along their own coast. Just how many ships comprised the Mexican Navy at this time is unknown, but the schooners Bravo and Vera Cruzana were the only two mentioned as stationed on the Texas coast in early 1836. In any case the Navy was small, and the diversion of even one or two vessels to protect Mexico's own shipping could — and did — prevent an effective blockade of the defiant state's seaports.

Meanwhile, more spectacular and dramatic events were taking place ashore. By the end of 1835, irregular Texas military forces had driven the Mexican garrison across the Rio Grande. Both sides began recruiting new, larger, and better-equipped armies for the more serious and bloody war they knew would ensue. The Texans relied upon adventurers from the United States, and they were not disappointed. Most of the men who died in the Alamo came to Texas in the winter of 1835-1836. Whole companies brought their own arms and equipment in chartered vessels from New Orleans and Mobile. By sea Texas grew swiftly in strength.

As for the Mexicans, President Lopez de Santa Anna came north from Mexico City, raised an army and took personal command of a three-pronged attack on Texas. His columns destroyed or drove before them virtually every vestige of the Anglo-American civilization. By 6 March 1836, the Alamo had fallen; a week later Goliad succumbed. The only sizable force remaining to the Texans was the haphazardly organized group of less than a thousand men under Sam Houston, the new Commander-in-Chief. This small army retreated steadily before Santa Anna's troops while keeping close to the sea and between the Mexicans and the fleeing women and children in what Texans termed the "Runaway Scrape." Texas appeared doomed.

However, Texas had begun to build a Navy. The General Council of the provisional government authorized a fleet consisting of four schooners on 24 November 1835. From this date the Navy of the Republic of Texas may be said to exist, although formal independence was not declared until 2 March 1836.

The first commisioned ship was the former United States Treasury cutter Ingham, which the Texans rechristened Independence. This small ship, only 89 feet in length, was commanded by Charles E. Hawkins, a former U.S. midshipman. Hawkins also became unit commander of other ships as they were acquired. Cruising between Galveston and Tampico during the first three months of 1836, he captured a number of small coasters and fishing craft and generally disrupted the vital seaborne communications of Santa Anna's army.

About twice as large as Independence, the second ship in this first squadron was the Brutus, commanded by Captain W. A. Hurd, the former master of the privateer William Robbins. The latter also was taken into the regular Texas Navy, renamed Liberty, and assigned to Captain W. S. Brown. His brother Jeremiah Brown received command of a fourth warship named Invincible. Hurd and the two Browns were former masters of small vessels which sailed the Texas coast. This experience made them ideal commanders in these early, rough, and ready days when local navigational and political knowledge was a definite prerequisite for success.

During the crucial months of March and April 1836, the four-ship "fleet" played a decisive role in preserving the independence which Texas had just proclaimed. On 3 March, W. S. Brown's Liberty was on a semipiratical cruise to Yucatan when she encountered the Mexican merchant schooner Pelican and captured her under the guns of the fortress at Sisal. The prize proved to contain 300 kegs of powder and other military supplies concealed inside cargo owned by the New Orleans firm of J. W. Zacharie. Pelican ran aground and was lost on the bar at Matagorda, Texas, but her cargo was salvaged and used to good advantage in the San Jacinto campaign.

A short time later, Liberty also seized the American brig Durango which was similarly loaded and falsely manifested. Brown's men appropriated her cargo and destroyed her.

During this period, Invincible captured the American brig Pocket, carrying contraband under a false manifest to the Mexican Army at the mouth of the Rio Grande. Her charter also included an agreement to carry Mexican troops to the Corpus Christi area.

Such action involving American ships, however, justified by the exigencies of the war effort, was bound to antagonize the United States. And, when Invincible sailed into New Orleans a few weeks after taking Pocket, Commodore Alexander J. Dallas USN, ordered her captain and crew arrested on charges of piracy. The naval charges were dropped several weeks later, but a civil suit remained in litigation for a number of years. Meanwhile, the Republic of Texas bought Pocket and used both her and her cargo against the Mexicans.

Every source of strength was desperately needed by the Texans, for in these early spring months, Mexico's armies were everywhere victorious. Santa Anna pushed northward, keeping close to the Gulf, and hoping to use the sealanes to provide him with logistic support. Throughout the campaign, the Mexican President kept looking for ships that never came. The activity of the small but active Texas Navy spelled the difference.

Finally, on 21 April 1836, General Sam Houston turned on his pursuer, penned Santa Anna's army against Buffalo Bayou which it could not cross — and completely destroyed it, capturing Santa Anna himself. Houston's soldiers justly received credit for the decisive battle of San Jacinto; but nevertheless the victory could not have been won — or the battle even fought — had temporary naval superiority not been achieved. Santa Anna was trapped due to his need to stay near the sea. Weakness afloat prevented his escape. He was inadequately supplied because his ships could not reach him.

Like the French fleet at Yorktown in an earlier American revolution, the Texas squadron did not see the final land battle. But neither the decisive engagement in 1781 nor the one in Texas 55 years later could have been fought successfully without the victor having first achieved at least a momentary naval superiority.

The defeat at San Jacinto forced the other two wings of the Mexican Army to withdraw from Texas. This retreat ended for all practical purposes any Mexican pretense of retaining authority in Texas — and made the task of reconquering it by land prohibitively difficult. The almost impassable arid area across northern Mexico and southwestern Texas served as an effective impediment to the use of land-power alone. The prevention of necessary communications between central Mexico and the Texas coast remained the key to successful defense of the new Republic.

Warship Invincible brought to President Burnet his first information of the victory at San Jacinto. Afterward, the little fleet continued its operations along the coast. Liberty escorted Flora when she took the wounded General Houston to New Orleans for hospitalization. While there Liberty, unable to meet her refitting bills, was detained in May 1836 and later sold to satisfy her creditors — an event which illustrated the shoestring budget under which the Texas Navy was forced to work despite the demands on it.

The other three vessels (Invincible, Brutus and Pocket) began a blockade of Matamoros at the mouth of the Rio Grande in an effort to interfere with attempts of the Mexican Army to return to Texas. In early September 1836, all three ships went to New Orleans or New York for overhaul because Texas lacked the industrial and commercial facilities to do the work locally.

A typically derring-do Texan incident occurred on 3 June 1836 when a detachment of twenty Texas Rangers captured three merchant ships near Corpus Christi. The Rangers, under Major Isaac Burton, had been scouting the retreating Mexican Army when they learned a strange ship was offshore. They enticed her to send a boat in and, in short order, captured the boat and the American vessel Watchman, which was carrying supplies for the Mexicans. Shortly thereafter, two more American merchantmen, Comanche and Fanny Butler, also came in with supplies for the Mexican Army. The Rangers surprised the crews and seized the ships. The Admiralty court at Velasco condemned all three vessels and their cargoes.

By the spring of 1837, while all three Texas warships were repairing in the United States, Mexico had a squadron of three brigs and two schooners blockading Galveston and other Texas ports. In their zeal to close the coast, the Mexican ships seized a number of American merchant vessels suspected of carrying contraband to the enemy. The United States consul at Matamoros requested naval assistance to protect the nation's shipping, and Commodore Dallas ordered Commander William Mervine's sloop-of-war Natchez to investigate.

Mervine entered the Rio Grande in time to witness the Mexican brig General Urrea escorting the captured merchantman Louisiana into port. He swiftly obtained Louisiana's release and then had a sharp engagement with the Mexican brigs, General Urrea, General Teran, and General Bravo, which were supported by fire from the Mexican-manned fort. Mervine closed the battle by capturing General Urrea and retaking the American merchant ship Climax. He took the former to Pensacola where Commodore Dallas ordered a court of inquiry to look into what he regarded as Mervine's precipitous action. He returned the Mexican brig and apologized for the incident.

On 17 April 1837, the Texas warship Independence, now commanded by George W. Wheelwright (Charles Hawkins had died of smallpox in New Orleans) , was entering the Brazos River when she was intercepted by the brigs of war Vencedor del Alamo and Libertador. After a skillful six-hour chase, Commodore Francisco Lopez forced Independence to surrender. Although Wheelwright was wounded during the engagement, his ship was so slightly damaged that she soon saw service in the Mexican fleet as the Independencia, thus flying her third national flag in two years. Before her career was over, she became a part of the navy of rebellious Yucatan and was even manned again for a few days in 1843 by the Texas Navy.

S. Rhodes Fisher, Secretary of the Texas Navy, had seen part of the battle involving Independence from the beach. He knew that President Houston and the Texas Congress were at odds over naval strategy. The Congress and the general public favored aggressive action, while Houston believed that if the Mexicans were not attacked, they would leave Texas alone. Fisher agreed with Congress and, without consulting the President, he went to Galveston where he ordered Brutus, commanded by J. D. Boylan, and Invincible, under H. L. Thompson, to sea. The audacious secretary accompanied the expedition as a volunteer, but he left Thompson in command of the two-ship squadron.

The cruise began on 11 June 1837; it was short, spectacular, and extremely controversial. The first stop was Mujeres Island, off Yucatan, which they claimed for Texas. During the process, the Texans stocked up on the abundant supply of turtles and departed without paying for them. Continuing up the Yucatan coast, the expedition boarded ships and landed shore parties until finally they were attacked by a cavalry force and driven back to their ships. The Texans burned two villages in reprisal, then tried to force Campeche to pay $25,000 in tribute. However, the city was surrounded by heavy stone walls and was well fortified. After an inconclusive three-hour exchange of gunfire, the two ships departed.

At sea the Texans met with more success — and diplomatic difficulty. They not only captured the small Mexican vessels Union, Telegrafo, Adventure, Rafaelita, and Correo de Tabasco, but also seized the British merchantman Eliza Russell. The latter action precipitated a serious diplomatic strain with Great Britain.

Sailing some of the Mexican vessels with prize crews and scuttling or burning the rest, Invincible and Brutus headed back for the Texas coast. They succeeded in evading a superior Mexican squadron off the coast until 27 August. Then the Mexican brigs Iturbide and Libertador sighted Brutus as she was entering Galveston Harbor, and Invincible anchored off shore awaiting high tide to go in. Although the exact characteristics of the Mexican vessels remain unknown, Libertador was said to have mounted sixteen 18-pounders. In any case, they were considerably larger and greatly out-gunned the Texans. Invincible ran aground in the poorly charted channel into Galveston, and Brutus beached inside the harbor while trying to come to her aid. Both later broke up in storms. The last two ships of the early Texas Navy were gone.

Nevertheless, their cruise was a strategic success because it had drawn Mexican blockaders away from the Texas coast for several vital weeks while men and munitions continued to pour into the new Republic. The longer the informal reinforcements in the form of individual adventurers could continue, the better Texas was able to gird itself against future assault. The existence of the Republic was still precarious, but life remained in it. In this sense, Texas seapower, whatever its shortcomings, was a success.

The year 1838 found Texas without any of the warships that had served her so well. Indeed, she was without any navy at all until Potomac, an old merchant brig, was purchased from L. M. Hitchcock of Galveston. It was an acquisition of dubious wisdom at best, for her entire service was as a station and receiving ship at Galveston. Inasmuch as there were few sailors to spare, Potomac served little purpose, constantly needing repair and requiring more men to keep her secure than she ever had available for transfer.

With its naval forces in such a state, Texas was saved from serious difficulty in 1838 by two circumstances beyond her control. The first was internal trouble in Mexico which required a concentration of security forces at home and diluted efforts that might have been made to retake Texas.

The second was the "Pastry War" between France and Mexico, so-called because one of its causes was a French baker's claim against the Mexican government. The conflict ended with the bombardment and partial destruction of Fort San Juan de Ulua at Vera Cruz and the capture of virtually the entire Mexican Navy by the French. Even though Vera Cruz was returned to Mexican rule when peace was restored in 1839, the French retained the captured warships. Thus, during 1838 the naval power of both Texas and Mexico became almost nonexistent.

III. The Texas Navy: 1839 to the End of the Lone Star Republic

While Mexico continued to refuse recognition and threaten reconquest, Texas found herself with a new president, Mirabeau Bonaparte Lamar (1838-1841), who was less inclined to await Mexican attack. Under Lamar's administration Texas reached a high watermark in nationalism, and official policy soared to its most daring heights. After the rejection of Texan overtures for statehood by President Van Buren, Lamar decided upon a course of complete autonomy for Texas. He entertained plans for a capitol, a national bank, and a state-run educational system. He would acquire the diplomatic recognition of major European powers, and support the independence of Texas with a military establishment of whatever size required.

A new Navy was created with first class warships and a professional officers corps. Six vessels were built in Baltimore for Texas under a contract signed with one Frederick Dawson on 13 November 1838. The cost of the ships was $280,000 — a sum which was not paid until long after Texas was admitted into the Union. They were well designed, built, and rigged; as late as 1848, American naval officers still commented on their fine lines. The ships were completed and delivered intermittently between June 1839 and April 1840.

In addition to these new sailing vessels, Texas purchased a large paddlewheel steamer named Charleston in 1839. Built in 1837 and closely resembling the merchant steamer Great Eastern, she was armed and rechristened Zavala, after the first Texas Vice President. She proved expensive to maintain, and it was difficult to find engineers to operate her in those early days of steam. Zavala's top speed was less than nine knots, and the navy's sailing ships were all considerably faster in a strong and favorable wind. Nevertheless, she was an important addition to the Texas Navy squadron, for she gave it a capability to operate in calm weather and on rivers.

The new commander of the Texas Navy was Captain Edwin Ward Moore, at 29 a veteran of fourteen years of service as an officer in the United States Navy. Usually known by his courtesy title of "Commodore", Moore was a thorough seaman, a dynamic leader, and a fiery fighter, completely imbued with an awareness that Texas must maintain or lose her independence at sea. The fleet he commanded was so completely dominated by Moore that his service and the Navy's history are inseparable.

After a period of recruiting, outfitting, and training, Moore's squadron — consisting of Austin, Zavala, San Bernard, San Antonio, and San Jacinto — was ordered to support the diplomatic efforts of James Treat to secure the recognition of Texas peacefully. Moore was forbidden to take any offensive action without Treat's concurrence unless attacked, and the Mexicans soon learned that Treat was not likely to resort to force and could be strung along indefinitely. Moore summed up the prospects in a hotly worded letter to President Lamar:

You may keep Treating with them until the expiration of your administration and will, in all probability, leave for your successor, whoever he may be, to reap all the advantages of your efforts; now is the time to push them for they were never so prostrate.

Nevertheless, it was not until a Mexican shore battery opened fire on a boat from Moore's flagship on 20 October 1840, and an unsuccessful and dying Treat departed Mexico, that the squadron was permitted to abandon the passive role it had maintained for three months. Moore quickly instituted a blockade with his small force and then struck at Mexico's "Achilles heel" on the Yucatan Peninsula.

Steamer Zavala towed Austin and San Bernard some 70 miles up the Tabasco River where, in conjunction with 150 rebellious Yucatecans, they forced the surrender of 600 soldiers defending the city of San Juan Bautista on 20 November 1840. It was the first time a steamer had been seen on the river. Moore demanded, and received, $25,000 in tribute for sparing the city.

At sea, San Antonio took one prize which was later sold for $7,000 and two smaller vessels. The remainder of the merchantmen boarded by units of the Texas Navy were released before the squadron returned to Galveston in February 1841.

It was a squadron that returned one less in number, and considerably more battered, than when it left — the most damaging foes during the cruise being accident and foul weather. The most serious incident occurred in October 1840 when San Jacinto, patrolling in the Arcas Island area instead of off Vera Cruz as ordered, broke the crown of her anchor in a gale and went aground with a gaping hole in her starboard bow. Despite every effort of Moore and the men of Austin, San Bernard and San Jacinto to save the stranded vessel, San Antonio broke up in a storm on 25 November 1840.

Zavala was badly, but not fatally, damaged on 3 October while at anchor off Frontera where she had landed a boatcrew to chop wood for fuel. A sudden storm struck and raged for three days while Zavala fought to survive. She lost her rudder, one wheel guard was crumpled and flooded; the crew had to resort to using furniture and her interior bulkheads as fuel to keep up steam. But in the end the superb seamanship of Commander J. T. K. Lothrop and his men saved her. A makeshift rudder and other fittings were completed by the resourceful sailors in time to lead the expedition to San Juan Bautista.

Zavala's return to Galveston was her last voyage. For want of about $15,000 for repairs, and a few men, the $120,000 steamer deteriorated, and was lost to the Texas Navy. She grounded at Galveston during a storm in June 1842 and was scrapped in 1843.

When Moore returned to Texas, he had expected merely to touch at Galveston to obtain authorization to resupply and ship new men at New Orleans in order to renew his operations against Mexico. He had enough money and, having been fired upon, he felt he had enough provocation for offensive ac tion. Instead, the government ordered San Bernard to return to Mexico. with another diplomatic agent, James Webb, to resume Treat's negotiations. Ultimately, the Webb mission met the same fate as his predecessor's — failure.

Meanwhile, Commodore Moore began a survey of Texas coastal waters in San Antonio. The survey lasted through the summer and fall of 1841; it was important work, albeit a more peaceful enterprise than Moore had hoped to be engaged in. The charts of the waters of the rapidly expanding Republic. were so inaccurate that one-fourth of the British vessels trading on the Texas coast in 1840 had been wrecked. Commonly used charts showed Galveston and Sabine Pass as much as 75 miles out of position and were inaccurate by as much as four feet in their indicated depth of channels. The survey information accumulated by the Texas Navy was used in British Admiralty charts and in those of G. and W. Blount of Baltimore. They remained the standard navigational tool until the U.S. Coastal Survey reached Texas more than a decade later.

During 1841, President Lamar determined upon an aggressive military policy. He reasoned that by launching land-sea assaults against Mexico he could achieve recognition of Texas independence, thus assuring peace and economic stability. However, his fiscal resources were lacking. The land phase of the attack, which became the ill-fated Santa Fe Expedition, was financed partly by the government and partly by private enterprise. The sea expedition was to receive financial support from Yucatan. An executive agreement between that rebellious province and Texas provided that the latter would furnish fully outfitted and manned ships to prevent the reconquest of Yucatan. In its turn, Yucatan would pay Texas $8,000 per month for the use of the fleet against a resurgent Mexico.

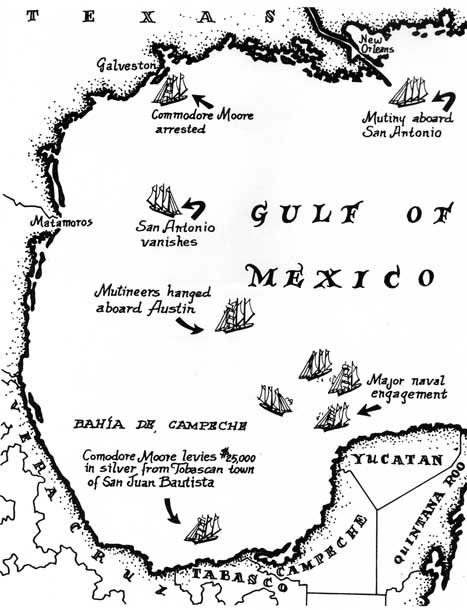

On 13 December 1841, the last day of the Lamar administration, Commodore Moore sailed for Yucatan with the Texas squadron consisting of his flagship Austin, San Bernard, under Lieutenant Commanding Downing Crisp ( a former British midshipman ), San Antonio, Lieutenant Commanding William Seegar and, much later, Wharton, Commander J. T. K. Lothrop. During a four month cruise in which hostilities were suspended several times while Yucatan negotiated for reentry into the Mexican Republic, the Texas squadron fulfilled its mission. It generally patrolled off Vera Cruz, challenging the smaller Mexican warships and capturing four Mexican merchantmen — Progreso, Doric, Doloritas and Dos Amigos. The cruise ended on 26 April 1842 on President Houston's orders after Yucatan had suspended its $8,000 a month subsidy during a truce with Mexico.

It was during this expedition that mutiny took place on board San Antonio. She had been sent to New Orleans to pick up provisions and men when the incident occurred. On the night of 11 February 1842, several of the ship's sailors and marines in a drunken rage tomahawked the duty officer and bayoneted him to death. After throwing three wounded officers down a hatch, they rowed ashore. Alerted by the noise accompanying the incident, the crew of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Jackson restored order, captured thirteen men and turned them over to civil authorities.

During the next year, the ringleader, Sergeant Seymour Oswald, escaped and another Marine prisoner died. Of the men tried by a general court martial, one was acquitted and another was pardoned. Three men received 100 lashes each, and four were sentenced to death. They were hanged from Austin's yardarms on 26 April 1843.

Upon the return of the Texas Squadron from Yucatan in April 1842, President Houston ordered Austin, San Antonio, and San Bernard to New Orleans and Galveston for extensive overhaul. However, he provided no funds for the repairs, much less for the necessary resupply of the vessels and augmentation of their depleted crews. A prolonged and intensely personal conflict between President Houston and Commodore Moore ensued.

Houston sought the annexation of Texas by the United States and used the

power of his office to prevent any action which might force Mexico to recognize

the independence of Texas. For more than a year he withheld all appropriations

from the Navy, but did not dismiss its commander. Moore, a member of Texas' war

party, used every means at his command to get his squadron into battle, while

publicly proclaiming the support of his president. Finally, when it appeared

that Moore might get his squadron to sea with the aid of New Orleans merchants,

Houston ordered Wharton, badly in need of repairs and desperately

undermanned, to New Orleans to be included in the detachment. As a last resort,

Moore sent San Antonio to Yucatan to ask that the naval agreement and

monthly subsidy be renewed. San Antonio, however, disappeared without

completing her mission. One unconfirmed report indicated that she was fitted out

as a pirate, but she was more generally believed to have foundered with all

hands in the great storm of September 1842, which also wrecked San

Bernard in Galveston.

Houston sought the annexation of Texas by the United States and used the

power of his office to prevent any action which might force Mexico to recognize

the independence of Texas. For more than a year he withheld all appropriations

from the Navy, but did not dismiss its commander. Moore, a member of Texas' war

party, used every means at his command to get his squadron into battle, while

publicly proclaiming the support of his president. Finally, when it appeared

that Moore might get his squadron to sea with the aid of New Orleans merchants,

Houston ordered Wharton, badly in need of repairs and desperately

undermanned, to New Orleans to be included in the detachment. As a last resort,

Moore sent San Antonio to Yucatan to ask that the naval agreement and

monthly subsidy be renewed. San Antonio, however, disappeared without

completing her mission. One unconfirmed report indicated that she was fitted out

as a pirate, but she was more generally believed to have foundered with all

hands in the great storm of September 1842, which also wrecked San

Bernard in Galveston.

During 1842, Mexico rebuilt its Navy. Two new schooners similar to San Antonio were ordered constructed at a cost of $75,000 in gold from the Brown and Bell Shipyard in New York City. One of them, Liberty, was wrecked on a reef off Florida while still manned by Americans in late January 1842. The other, Aguila (Eagle), was armed with seven Paixhans, effective 42-pounder shell guns. At about the same time, an unarmed seagoing tug renamed Regenerador provided the Mexicans with added mobility.

During the year Mexico also added to her fleet at the expense of Yucatan. Before the Texans departed Yucatan in April 1842, Commodore Moore had warned authorities there to safeguard their warships in the event that the truce with the central government proved temporary. The vessels were demasted and their sails sent ashore. Even inadequate watches were posted. Moore's prophesy proved correct. Hostilities reopened on 5 July with a skillful and daring operation in which the Mexican Commander Tomas Marin led 57 officers and men on a surprise attack. Stealthily — and possibly with the aid of bribery — they boarded and captured brigantine Yucateco, which was armed with 16 guns. Marin took her into the Mexican Navy as Mexicano and, in conjunction with army troops, used her on 22 August to capture Iman, a 9-gun brig, and the 3-gun canoas, Campecheano, and Sisaleno. These successes reversed the relative naval strengths of Mexico and Yucatan.

Far more ominous for Texas was the purchase of two modern sidewheel steamers from England. Guadalupe was 775 tons, 200 feet long, and had engines of 180 horsepower. She was armed with two great 68-pounder Paixhans pivot guns, each capable of hurling an explosive shell a mile and a half, and two 32-pounders. She is said to have been the first steam warship to be built of iron, and boasted watertight compartmentation, another innovation of the period. The other steamer was Moctezuma (or Montezuma). Built of wood, she was a larger ship of 1,111 tons and 204 feet in length. She had engines of 280 horsepower. In addition to two 68-pounder Paixhans, Moctezuma mounted six 42-pounder guns, all much larger and of longer range than the weapons of the Texans.

Most of the officers and many of the crew were British; Guadalupe's captain was a commander in the Royal Navy on leave, the captain of Moctezuma had resigned from the British Navy to take command. However, the sailing of these two ships was delayed by the same type of resourceful diplomacy which was later used against Confederate vessels in England during the Civil War. Guadalupe and Moctezuma were not actually delivered to Mexico until the winter of 1842.

The Texans followed the Mexican example and copied the Paixhans shells for use in their own 18-pounders. This new kind of shell, invented by a French Army officer, contributed importantly to a revolution in naval construction and warfare by forcing the installation of armor. The solid shot used heretofore would drive holes in a ship's sides; Paixhans shells, exploding within a ship, could be more destructive. They had been fired in tests but had not been used in action between ships; thus, naval experts in Europe and the United States observed the coming conflict with great curiosity.

Meanwhile, for various reasons including the bitter Moore-Houston feud — the Texas Navy declined while that of the Mexicans improved. By the autumn of 1842, Texas had only two ships — Austin and Wharton — capable of going to sea, and they were in New Orleans almost destitute of men and in grave disrepair.

The revitalized Mexican Army and Navy vigorously undertook the task of reconquering the wayward provinces. British and American observers, as well as Texans and Mexicans, reported in their correspondence that Yucatan would be subjugated by the spring of 1843 and Texas would swiftly follow. As reports reached New Orleans, Moore, still commanding the Texas Navy, resolved to go to Yucatan's aid rather than do nothing and leave Texas to fight alone later on. While President Houston publicly agreed with this strategic decision, he privately acted on the premise that Texas was too poor to support a Navy and that offensive operations would only antagonize Mexico at a time when he was negotiating with the United States and Great Britain for their help in securing a permanent peace.

Moore was undaunted. Receiving financial help from Yucatan and local businessmen, he got Austin and Wharton underway on 19 April 1843 during, as one of the midshipmen described it, "a moonless night black as a crow's wing." As the Texans passed the American sloop-of-war Ontario, the U.S. crew manned her yardarms and gave three cheers for the Texas Navy! Moore wrote that "the officers and men are all eager for the contest. We go to make one desperate struggle to turn the tide of ill luck that has so long been running against Texas."

The odds were indeed high. Austin carried sixteen 24-pounders and two 18-pounders, while Wharton mounted fifteen 18-pounders. Allied with them, and primarily commanded by Texas officers, was a small Yucatan squadron including the 5-gun Independencia and five gunboats carrying one gun each. Opposing them was a formidable Mexican fleet led by the Paixhans-armed steamers Moctezuma, which also had six 42-pounders, and Guadalupe, which carried two 32-pounders. Mexicano (ex-Yucateco) was rated 16 guns; Aguila mounted seven Paixhans; Iman had nine guns, and Campecheano carried three guns. In addition, there were several other vessels of varying size, including the steamer Regenerador.

The Mexican squadron had a decided advantage, not only in the number and size of guns, but in range as well. There would be a distance of approximately one-half mile in which Mexican shells could strike Texas vessels while Texas guns could not reach their opponents. Moreover, the fact that three Mexican ships were steamers would allow them to open or close the range at will in calm weather or avoid action entirely.

Nevertheless, Moore would not concede the initiative to his foe. As he completed his preparations for sailing from the Mississippi River, an American merchant ship arrived and reported that Moctezuma was embarking troops alone at Telchac, 150 miles north of Campeche. Seeking to take advantage of the opportunity of engaging the steamer with the numerical odds in his favor, the Texas commodore swiftly set sail with Austin and Wharton for Telchac. But he was just 24 hours too late. On 16 April the Mexican consul at New Orleans warned Commodore Lopez of Moore's imminent departure, and Lopez recalled Moctezuma before the Texans could reach her.

Austin and Wharton proceeded toward Campeche, hoping to overtake Moctezuma enroute. On the evening of 29 April, they anchored off that port and Commodore Moore ordered an attack on the gathered Mexican forces at first daylight when the breezes would be most favorable. As a precaution, he ordered his two ships to prepare for their own destruction by detonating their magazines if capture appeared likely.

Dawn of 30 April disclosed five Mexican ships — Moctezuma, Aguila, Mexicano, Iman, and Campecheano — about ten miles to the south, and Commodore Lopez's flagship Guadalupe coaling at Lerma, several miles to their east. Moore sailed toward Guadalupe to take advantage of an east-southeast wind in an effort to get between the flagship and the rest of the squadron. The squadron darted out quickly, but Guadalupe was slow getting underway. Unknown to the Texans, Captain Cleveland of Moctezuma had died of yellow fever during the night and about 40 crew members were incapaciated by the disease.

The two forces maneuvered from 4 a.m. until 7:35 without firing as the Texans attempted to close range and the Mexican steamers, now operating together, paddled up wind of Austin and Wharton. The Mexican sailing vessels were four to five miles to windward.

At last the Mexicans opened fire with their Paixhans, but with little effect. At first the shells fell short, and then carried over the two Texas warships. About 9 a.m. a calm set in and Austin and Wharton ceased firing. With his sails limp, Moore anchored, served grog to his tired men, and rigged springs to his anchors so that he could shift the ships' heading if the steamers attempted to press their advantage and attack the immobile ships.

It was two hours, however, before the Mexican steamers reopened the engagement. Moore's flagship replied at once. As a breeze came up, both Texas ships got underway and again sought to divide the Mexican forces. During the battle, Austin took a direct hit from a 68-pound shell, which cut a shroud, smashed through Moore's cabin, and passed out the stern. Fortunately for the Texans, it did not explode, and it was the only damage the flagship sustained. Wharton suffered two killed and three wounded. Mexican losses were probably heavier. Spy reports indicated that Moctezuma had thirteen killed, while Guadalupe lost seven men in the engagement. At 11:40 both sides ceased firing, and the Texans entered the Yucatan port of Campeche.

If the action was not decisive, it nevertheless accomplished a great deal. The Mexican siege of Campeche was broken, permitting coastal vessels to enter under the protection of Moore's guns. Supplies, men, and munitions for the Mexican Army now had to be landed 15 miles away at an open roadsted. The Yucatecans were encouraged to hold out.

The Mexican Government was incensed. Lopez was stripped of command and arrested. The new commander, Tomas Marin, protested that his ships were undermanned, in poor condition, and infested with yellow fever. The Army commander, General Ampudia, was directed to furnish him with sailors to fill out his crews. Marin laid up Mexicano and another vessel as a means of getting enough experienced men to sail his other ships. He dispatched the smaller, less heavily-gunned ships to clear the area and retained only Moctezuma, Guadalupe and Aguila. When many of the British sailors refused to continue their contracts, he borrowed more soldiers from the Army. Moore meanwhile sought to resume the action. Austin obtained two 18-pounder long guns and Wharton a long 12-pounder from Campeche's shore installations. Moore wrote,

"If I had a steamer here, I would give

ten years of my life, as with it I could get

close action and decide the Fate of Texas."

He had good reason to lament his lack of mobility; each morning for the next three weeks his two vessels prepared for action, but the wind on which he had to depend was not strong enough for a sortie.

Finally, on 16 May 1843, morning breezes came from the east, enabling the Texans to bear down upon the Mexican steamers. Yet some three miles from the enemy, Austin and Wharton were suddenly becalmed. The Mexicans moved in, firing their 68- and 42-pounders while the Texans' smaller 24's and 18's could not reply. For more than two hours shell explosions hurled fragments into the sails and among the Texas gunners. Then, Moore detected a small puff of wind, trimmed his sails to it, and maneuvered between the startled steamers before they could withdraw. For three hours he forced Moctezuma and Guadalupe down the coast, taking 14 hits and suffering 3 killed and 22 wounded in his crew of 150. But his flagship's guns blasted the Mexicans steadily, inflicting a terrible toll. According to the reports of spies and deserters, Guadalupe had 47 killed and about 100 wounded, and lost the use of one of her paddles during the battle. Moctezuma suffered some 40 casualties, including her captain.

In all, Austin fired 530 rounds, almost exhausting her magazine, before the Mexicans paddled up wind and broke off the action.

These two engagements marked the first time exploding shells had been used in action at sea and the only known instances in which sailing ships defeated steamers.

Wharton (which had been unable to close to take part in the battle) and Austin returned to Campeche. The latter, badly cut in her rigging, also had a hole below the waterline on the starboard side and had taken three feet of water in the magazine. Although both navies required repairing and neither had enough ammunition for a renewed, sustained encounter, the Texans gamely continued to sortie in the days that followed. The Mexicans were forced to remain far enough at sea for Texan supply ships to reach Campeche. Thus, the city was able to withstand the assault of the Mexican Army ashore.

Then, on 26 May, word reached Campeche that President Houston had declared Moore's cruise illegal. He castigated the Commodore as a pirate, murderer, mutineer, and embezzler. Stunned by Houston's assertions, Moore sent what he hoped was proof that his actions were justified and awaited further instructions. Although a new supply of powder arrived on 16 June, he received no further word from Texas. A week later the Mexican squadron broke off the seige of Campeche and withdrew. Against large odds, Moore had won the test of strength. Yucatan was not reconquered; and Texas was spared the invasion that surely would have followed had Mexico won the battle of Campeche. Later, the United States and Great Britain secured a truce between Texas and Mexico which endured throughout the existence of the Lone Star Republic.

Moore returned Austin and Wharton to Galveston where the public gave him a tumultuous reception and President Houston dismissed him from the Navy. Ironically, Captain Marin was awarded a special Cruz de Honox.

Texas maintained its precarious existence for three more years, primarily under the protection of United States soldiers and sailors. Men of the Texas Navy were discharged without pay and the remaining ships were allowed to deteriorate. Moore and Lothrop, Wharton's commander, pressed for a trial on the charges contained in the piracy declaration. Lothrop died before being vindicated, but Moore was exonerated by a court martial.

When Texas entered the Union, Austin, Archer, Wharton and San Bernard were transferred to the U.S. Navy; however, because of their poor condition, all were scrapped by 1848. Moore and many of his fellow officers attempted to enter the American Navy, but they had to be satisfied with half pay for five years. One midshipman, Edwin F. Gray, entered the Naval Academy in 1846 and served in the United States Navy until 1857. It is also likely that some of Texas Navy's enlisted men shipped into the U.S. Navy.

The contributions of the Texas Navy to the Republic were more important than contemporarily understood. During the critical first months of revolution, the Navy fought off blockaders, interrupted Mexican supply lines, and provided the opportunity for the victory at San Jacinto. Later, aided by American and French quarrels with Mexico, it prevented a seaborne or sea-supported attack of Texas. And finally in 1843 the Navy thwarted a well-organized, full scale invasion of Yucatan which, if successful, would have led inevitably to reinvasion and possibly reconquest of Texas.

Moreover, the Texas Navy set a tradition for bold, aggressive, and imaginative action which paved the way for future American action in the area. Following the admission of Texas to the Union in late 1845, the Nation became embroiled in its own war with Mexico. Once again, seapower was the key to victory. When General Zachary Taylor's Army in northern Mexico was thwarted by logistics problems similar to those which had earlier prevented Mexico's reconquest of Texas, the United States adopted a maritime strategy. In addition to general mastery of the seas, it involved successful amphibious attacks on Mexican ports in the Gulf of Mexico and in California. The Navy closely coordinated its operations with those of the Army in achieving victory in the nation's first large-scale battle on foreign soil.

These operations, to which the action of the Texas Navy served as a prelude, provided a pattern for future joint operations which continue to he a point of pride to the Navy and Army — and an essential part of the nation's power as has been witnessed repeatedly in cold and hot war since World War II.

Ships of the Texas Navy

1810-1821 |

Mexico revolts against Spain and forms a Republic. |

1820-1830 |

United States citizens immigrate to Texas. The Mexican government tries to control the influx. A groundswell of feeling for Texas independence develops. |

1834 |

President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna dissolves the Mexican Congress. |

1 September 1835 |

Texans in merchant ships San Felipe and Laura seize the Mexican treasury vessel Correo de Mejico. Mexican public opinion is inflamed, but the coasts of Texas remain open. |

1 November 1835 |

Texas revolts against Mexico. A centralized government is established under Stephen Austin and Sam Houston. |

24 November 1835 |

The Texas General Council creates a Navy, authorizing a fleet consisting of four schooners. |

19 December 1835 |

Privateer William Robins recaptures the American schooner Hannah Elizabeth, which had been seized by Mexico. The incident compels Mexico to send its shipping in convoy. |

Winter 1835-1836 |

The Mexican Army, unable to secure logistic support from the sea, is driven from Texas. The Texas Navy captures several small coasters. In the Spring, Lopez de Santa Anna leads the Mexican Army back into Texas. |

2 March 1836 |

Texas declares her independence and proclaims a Republic. |

3 March 1836 |

Texas schooner Liberty captures Mexican schooner Pelican off Sisal, Yucatan, with contraband gunpowder. |

6 March 1836 |

The Alamo falls. |

3 April 1836 |

Texas schooner Invincible captures American brig Pocket carrying contraband under a false manifest to the Mexican Army. |

21 April 1836 |

General Sam Houston's Army wins the battle of San Jacinto as the Texas Navy prevents support from reaching Lopez de Santa Anna, who had to stay near the sea for logistic support which never came. |

3 June 1836 |

Texas Rangers capture three merchant vessels with supplies for the retreating Mexican Army off Corpus Christi. |

September 1836 to April 1837 |

Independence, Brutus, and Invincible of the Texas fleet undergo overhaul in the United States. |

17 April 1837 |

Independence is captured off Galveston by two Mexican brigs. |

June to August 1837 |

Brutus and Invincible cruise off Mexico, capturing five ships in a highly successful voyage which carries the conflict to Mexico's sea frontier. |

27 August 1837 |

Brutus and Invincible are forced aground near Galveston by Mexican man-of-war, robbing the Texas Navy of its last battle-worthy units. |

13 November 1837 |

Frederick Dawson of Baltimore contracts to build six vessels for the Texas Navy, as officials recognizing the need for seapower move to rebuild the Lone Star fleet. Ships San Jacinto, San Antonio, San Bernard, Louisville, Wharton, Austin, and Archer are delivered one by one between March 1839 and April 1840. |

20 June 1840 |

The Texas Squadron, commanded by Commodore Moore, sails for Mexican waters to "show the flag" in support of vain diplomatic efforts to secure peace. During the lengthy cruise San Jacinto is stranded at Arcas Island, but three other ships capture the city of San Juan Bautista, seventy miles up the Tobasco River. |

Summer and Fall 1841 |

San Antonio surveys the Texas coast, providing charts of the area for the first time. |

17 September 1841 |

Texas and the dissident Mexican province of Yucatan conclude a naval agreement which provides the Lone Star Republic with an ally and divides Mexican war effort. |

13 December to 26 April 1842 |

In a lengthy cruise spurred by Commodore Moore's resolute determination to launch an offensive against Mexico, the Texas squadron captures four ships and causes consternation among Mexican shipping interests. |

September of 1842 |

San Bernard and San Antonio are lost at sea in a gale. |

January to December 1842 |

Impressed by Texas' achievements with limited power at sea, the Mexicans rebuild their fleet. |

13 April 1843 |

Austin and Wharton relieve the siege of Campeche, Yucatan, after vigorously engaging a superior Mexican squadron. This bold action encourages Yucatan to continue her struggle against Mexico. |

16 May 1843 |

The Battle of Campeche concludes with both sides battered, but only Commodore Moore's two ships are willing to renew action. Within two weeks, Moore is recalled to Texas and his cruise is declared illegal by President Houston. |

14 June 1843 |

Austin and Wharton return to Galveston; the conflict continues as United States sailors and soldiers keep a watchful eye on the Mexicans. |

29 December 1845 |

Texas is formally admitted into the Union. |