TUNISIAN CAMPAIGN

OUSSELTIA VALLEY OPERATION

Following postponement of Satin, General

Eisenhower concurred with General Alexander and his Combined Chiefs of Staff that the 1st

Armored Division would be employed to defend southern Tunisia and deter any energetic

offensive by General Rommell when his Afrika Corps arrived in Tunisia as it fell back from

British 8th Army attacks. Following postponement of Satin, General

Eisenhower concurred with General Alexander and his Combined Chiefs of Staff that the 1st

Armored Division would be employed to defend southern Tunisia and deter any energetic

offensive by General Rommell when his Afrika Corps arrived in Tunisia as it fell back from

British 8th Army attacks.

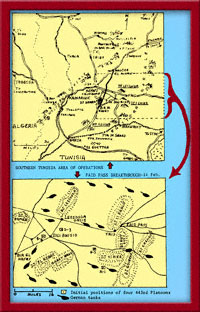

In order to extricate the surrounded French units the 1st Armored Division’s

Combat Command A (CCA) prepared to attack Fondouk on 23 January and Combat Command B (CCB)

under General Robinett was sent to the Ousseltia Valley. The 1st Infantry Division’s

26th Regimental Combat Team, protected by 443rd Platoons D-1, D-3, D-4 and D-5, attacked

the ridge before Ousseltia, gradually wiping out German and Italian pockets of resistance

and forcing the enemy to withdraw thus relieving pressure on the hard-pressed French

units. The 26th Regiment then drove through Ousseltia Pass taking 450 Italian prisoners.

During the action Platoons D-1 and D-5 engaged eight Messerschmitts (ME-109s) strafing

from 1000 feet and destroyed two planes. This drive brought the Allied forces to within 40

miles of the major German headquarters and supply base 20 miles southeast of Kairouan.

Thus threatened, the Germans began to retaliate viciously, first by air and then by land.

The German Air Force controlled the Tunisian skies at this point and usually attacked

Allied positions around mealtimes. Stukas (JU-87s) had fixed landing gear and used their

screaming sirens to frighten and demoralize our troops as they dove strafing and bombing

from out of the sun. Often the ME-109s would tantalize the AAA gun crews by staying just

out of range of the gun-tracks but drawing their fire so that Stukas coming out of the

blazing sun could strafe and bomb the tanks and infantry. Major Larson immediately secured

Navy variable polarized glasses for the gunners, gun sergeants and platoon leaders.

Success against Stukas increased and the 443rd’s T-28-E1s became known to German

pilots as the "Hornets’ Nest". At other times, ME-109s would drop smoke

bombs and the Stukas would come out of the smoke, laying their "eggs". Another

tactic was for the Germans to send one or two planes in at very low altitudes, where

angular speed for tracking by the gun-tracks would be the greatest, just to draw fire and

determine the amount of antiaircraft defense. If they didn’t draw too much flak the

main body of planes would appear and attack in 10 to 20 minutes.

A sensing of the kind of combat experienced by men of the 443rd may be gained from

action reports from Platoon C-4.

"During the day we were constantly on alert for planes and we moved in blackout at

night, to new positions. Everyone was worn out but we kept awake. I can still see those

planes overhead. We fired and fired. We were scared! There were raids every 20 minutes and

we thought the day would never end. They kept this up for days but did little damage as we

kept knocking them down. They began to respect our guns and stayed out of range. But those

88 mm shells! The whole crew was really afraid of them. No sooner did we move to new

positions than the Germans would start shelling us and we leaped into our foxholes, saying

our prayers".

Typical of the many combat moves of the 443rd platoons was that during the advance with

the 26th Regimental Combat Team from Sbeitla to Ousseltia during night-time hours in

January 1943. The grueling, cold, blackout move over steep, tortuous mountain passes often

required the gun-tracks to back up in order to negotiate the many hairpin turns. Most

unsettling was the sight of native French Army troops, with night campfires blazing away,

blatantly signalling their whereabouts to the enemy. Americans, carefully schooled in the

art of concealment and camouflage, could only gasp and curse at such action. But as time

went by, they too developed a "what the hell" attitude but never to the extent

of their French allies.

With the drive through Ousseltia Pass by the 26th Regimental Combat Team, Platoon D-1

was ordered to protect the mouth of the pass from German attempts to close it and trap the

26th. Steep cliffs at the entrance to the pass made the task almost impossible but the

gun-tracks were soon in the best available positions - three in the hills at the entrance

to the pass and one on the plain at the entrance itself. The 443rd men didn’t have

long to wait. In a morning attack, six ME-109s roared in to attack and while the planes

were still out of range the anxious AAA gunners began firing even before they were spotted

by the enemy. The ME-109s then broke into pairs and sprayed the gun-tracks unmercifully

from several different directions. Terrain and position allowed the gun tracks,in the

hills, limited fields of fire and they were unable to give protective fire to the single

gun-track on the plain,at the entrance to the pass. A second attack failed when heavy AA

fire caused bombs to be dropped wide of their marks. 443rd men learned a costly lesson

that camouflage was important and that antiaircraft fire should not begin until either the

gun-track positions were seen by the enemy or the planes were well within range of the

weapons. While such tactics had been stressed in training, real and sharp learning seemed

to come best in combat action. Platoon D-1 shot down two of the attacking ME-109s, at the

cost of one man killed and seven wounded. Two gun-tracks were put out of action. They were

later retrieved and repaired. But the Ousseltia Pass and Valley remained open and in

Allied hands.

|