THE INVASION OF SOUTHERN FRANCE At 0800, August 14, 1944, the chateau-studded Riviera, its pastelled hotels and white-bleached beaches, its oleander and terraces, its coastal drives that drop like cornices over the cliffs, lay invitingly ahead. But if this was the season, it was not the year for an influx of smart Parisian loungers. It was the day for plebeian GI Joe from Tahoka, Texas, and all U. S. points east and west to crash in on an Allied invasion that was to succeed in tactical perfection.

The under-belly blow to Nazi-dominated Europe, long contemplated in the minds of the Allied Command, was first proposed in December, 1943. The plan, a coordinated double jab at both Northern and Southern France during May of 1944, had to be modified when the gruelling Italian campaign lingered. Postponement of the attack in the south became necessary. DECISION MADE LATE During the early summer, when an August date for the Riviera invasion was proposed, 36th Division troops were pushing up Italy’s coast nearing the Germans’ Pisa-Rimini defense line. Not until June 24 was the 36th finally nominated for participation in the Southern France project. Withdrawal from the line followed a few days later to allow a rushed-up program of invasion training for the Division on the beaches near Salerno. By late July in Normandy the breakout at St. Lo was developing and the onrushing drive toward Paris would follow. In Southern France, German forces in defense of the coastal areas were being reduced to meet the serious breaches in the north. Our intelligence determined that the German Nineteenth Army, soon to oppose the Allied invasion, had been streamlined from 13 to 9 divisions—still, however, an effective force if it could be concentrated. With the Luftwaffe weakened and the German Navy, never top-notch, practically eliminated, our forces, strong in these departments, entered the operation with confidence. ANYONE COULD SEE As Lieutenant General (then Major General) Alexander M. Patch’s Seventh Army and the VI Corps assault team—the veteran 3rd, 36th, and 45th Infantry Divisions—prepared for D-Day, concentrations of Allied might lay daringly in Mediterranean ports, principally Naples. That this was the prelude to an invasion obviously was implied to the Germans. Furthermore, Southern France was a very logical target. But if the enemy sensed what was coming, he did not know at what specific points our troops would strike.

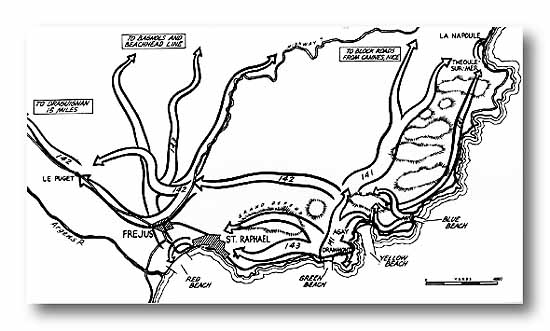

The plan finally adopted was to have the 141st Infantry assault Green Beach with two battalions and Blue with one at H-Hour, 0800, to secure these beaches, capture Agay and protect the Division right. The 143rd Infantry was to follow immediately behind the 141st and then drive to the west to seize the heights overlooking San Raphael and Red Beach, thus assisting the 142nd. This regiment was to land six hours later, assault Red Beach, and, together with the 143rd, capture San Raphael, the airfield and Frejus. From the beaches troops were to press inland to a depth of 12 miles, block any enemy attacks from the Cannes area on the right, and push up the Argens River Valley on the left to contact a paratroop force dropped near Le Muy. The capture of Frejus and the small port of San Raphael were "Must" jobs that had to be accomplished immediately. CONVOY SAILS

Taken by surprise, the Germans did not bring their machineguns into action until the fourth wave had landed and then it was too late. By 1000 hours Drammont and Cape Drammont, surrounding Green Beach, were reported clear. Casualties had been extremely light. Pushing north through Agay, the 2nd Battalion encountered resistance round-about the defenses of Yellow Beach. The 3rd Battalion seized the high ground directly north of Green Beach. The enemy offered heavier resistance on Blue Beach where several anti-tank guns opened up on incoming landing craft of the 1st Battalion, 141st. This resistance was rapidly overcome and the battalion pushed in to drive the Germans from craggy dominating heights, 1,200 Germans surrendering to the invaders. The 1st Battalion won a Presidential Unit Citation for this action. Immediately following the 141st, Colonel Paul Adams’ 143rd Infantry landed in a column of battalions on Green Beach; the 1st at 0945, the 2nd at 1000, the 3rd at 1035. "Grand Defend," the high ground to the northwest, was immediately seized by the 1st Battalion. The 143rd then began to drive west, paralleling the shoreline, for San Raphael. GRAVE DECISION Meanwhile, at 1100 hours the 142nd Infantry loaded into assault boats and headed for Red Beach which it was to strike at 1400. From early morning enemy defenses here defiantly rebuked all efforts to soften them up. Naval craft nearing the beach for mine-detection were fired upon and sunk, and from San Raphael and the hills beyond Frejus, the beaches remained covered by flanking enemy fires.

Landing of the 142nd began on Green Beach at 1530 in accordance with an alternate plan which had been previously prepared. Colonel G. E. Lynch’s regiment swung in an arc north and west over the mountains between the 143rd and the 141st to attack Frejus from the rear. The 143rd was ordered to clear Red Beach from the rear after it had seized San Raphael. There was no let-up during the night as plodding infantrymen strained inland to broaden the beachhead and win, assigned objectives. Both Frejus and San Raphael were cleared in a flurry of fighting in the early morning by the 142nd and the 143rd. Red Beach was secured. On the right in the more frequented resort country of the Riviera the 141st surprised Germans six miles inland driving with glaring headlights along the Cannes-Frejus highway and placed blocks on all roads to Cannes near La Napoule. The only serious setback was the sinking of an ammunition and artillery-laden LST by a single low-flying plane in the channel off Green Beach at dusk of D-Day. PARATROOPERS CONTACTED On the night of the 16th the 142nd broke the last German block before Le Muy in the Argens valley. Next day the paratroopers, who had jumped nearby, were contacted and Draguignan was entered. In the town the Commanding General of the German 62nd Corps, completely befuddled by the sharpness of the Allied attack, was nabbed along with his entire staff.

100 MILES IN ONE DAY The 36th extended its lines 100 miles in a single day while racing to outrun the German Nineteenth Army still in the Marseilles-Toulon area. Grenoble, famed French mountain resort 200 miles from the beaches, fell to the 143rd on August 22, one week after the landing. French Forces of the Interior, well-organized patriots harassing the enemy from the rear and controlling vast stretches of territory, greatly contributed to the success of the Allied in vasion of Southern France. After the operation Allied Headquarters boasted of the Riviera Invasion: "A model of effective organization, cooperation of all services, and vigor of action—one of the best coordinated efforts in all military history." Its beachhead was the largest to be created in three days during the war. The entire 36th, less one battalion, had landed on one narrow beach. Its casualties had been exceedingly light and the aggressive assault had completely disrupted the enemy’s defenses and communications. After his weak defense had been shattered, the enemy was never given an opportunity to recover. The drive north to Grenoble paralleling the Rhone Valley succeeded magnificently. Forced to fall back, the Germans were also prevented from making any thrust over the mountain passes from Italy. Not in any preceding operation had the mobility of an infantry division been so tested and utilized.

|