WICK FOWLER'S

DISPATCH

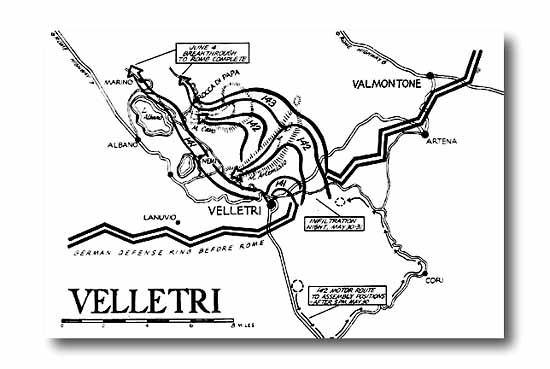

Velletri, Italy, June 2 - Texas' 36th Division, led by Major General Fred L. Walker, socked this Nazi stronghold Friday in one of the most brilliantly executed maneuvers of the entire Italian campaign, sweeping in to take the town and then continuing on the march to Rome. Infantrymen, backed by tanks, tank destroyers, artillery, engineers and supply trains swept into Velletri from the east, north and northwest while other Fifth Army troops held the jaws on a trap set for retreating Germans and while Allied artillery cut the Nazi escape route on Highway Seven. There still remained half an hour of daylight when the troops entered the town but the men made good use of the time to mop up German snipers and other defenders caught in the squeeze play. Two British correspondents and I followed General Walker while he led the attack. We did not know when we left a regimental command post high up in the Alban Hills that we would be spearheading the drive. We walked along a macadamized highway lined with tall trees and villas, each seeming to hold German snipers. Many were bypassed but there were 200 bodies scattered here and there. Our riflemen worked the area in long skirmish lines far to our left and right and fired blindly into possible enemy hiding places, a new tactic the division developed and used in this attack for the first time. There were hidden machine gun nests and we could hear the burp of the mean German machine pistol. Because so many of the enemy had been passed up, the danger in moving forward didn't appear to be much greater than going back. The infantry tactics reminded me of a Texas jackrabbit drive, only this time the rabbits fought back. The Italian houses offered good protection for last-stand Germans. Rifle fire made a continuous crackle. General Walker - this was his show - was apparently oblivious of the special dangers accorded a two-star general with insignia plain to any hidden sniper. He moved among the men, his pistol bolstered, and directed them as though he were playing chess back at division headquarters. He knew where every unit was and he knew just how he would play the game to take the long-stubborn fortifications. Occasionally, a lone machine gunner or rifleman would come up and the general would say to him: "Get over there, now. Hurry up," he said pointing, "they need you there." He never raised his voice. Lt. Col. Hal Reese, of Philadelphia, the general's executive officer in the last war and his inspector general in this one, was with us. Reese occasionally moved ahead of the first infantry and TDs. Walker cautioned him several times.

TANK FIRE AND PRISONERS Within site of Velletri snuggled on a low hill, we got under German tank fire. Four Tigers were zeroing in the road junction where we stopped to pick up prisoners. Our tank destroyers moved upon a low bank by the road and a duel, continuous and heavy, went on for fifteen minutes. The TDs had to cut down a house to get at the hidden Tigers which stuck their noses out, fired and withdrew. The Tiger 88 shells came in close. We hit the ditches, ignoring possible anti-personnel mines. The German prisoners likewise hit the dirt.

WAITING AND WONDERING We watched our wrist watches. The minutes ticked off slowly. We could hear big shells but they weren't close. Four minutes passed, then five, then six. General Walker crawled out. "Looks like he got through in time," he said. I shall always want to meet that messenger and shake his hand. We moved up a little. Three Germans stepped out and surrendered to General Walker. He began gesturing to them to find out where others were hiding. They pointed to a villa few hundred yards to the north. He said, pointing, "Go get them." The German went off. The general sent a soldier with him so the captive wouldn't be shot by our own troops or recaptured. They soon returned with twelve more Nazis. They were youngsters. We had 130 by this time. General Walker loaded a German litter case on his jeep, piled four prisoners on it and sent his driver, Sgt. John Clay, of Austin, Texas, back to the rear with them. Then an officer stepped up to the general, saluted and whispered for a moment. General Walker shook his head as though shocked. He had got word that a German tank shell had killed Col. Reese just ahead of us. "I told him not to get too far out there," he kept saying. We later learned that Reese must have had a premonition that he wouldn't live through this operation. His notebook carried a freshly written notation to notify his brother if anything happened to him and advised disposition of his personal effects.

DOG-TIRED DOUGHS For three nights our troops had only snatches of sleep stretched out on the ground. They were weary and dogtired-infantry style. But they had the Germans on the run and that alone gave them the energy they needed. If they had to fight they would rather have the odds in their favor for a change, or. at least a 50-50 chance.

It was the same sort of flanking move that General Walker advised the higher command to let him make at Cassino before the ill-fated Rapido River crossing. After the Rapido fiasco failed, Fifth Army troops did flank Cassino to the North but a high cost had been paid. Even as the Fifth Army fought stalemated before Velletri with Rome only twenty miles away, General Walker was developing the encirclement plan. It was fantastic - except to a few.

ENGINEERS COUNTED ON The higher echelons said he couldn't get roads built through the steep, heavily-wooded Alban Hills to get big guns, tanks and supplies in support of the foot soldiers. General Walker insisted that his engineers could do the job. They did when the signal to go ahead finally came down. If it failed we would lose thousands of men. Walker said it would not fail. We believed him. Within two hours the brilliant tactical operation was put into effect. While combat engineers of the 111th Engineer Battalion and other fighting men held the stopgap before Valletri the main bodies pulled back, loaded onto trucks and moved into an assembly area. Then by foot they began the all - night march to high points up in the hills held by a few small German units as outposts. The Nazis never dreamed that the Americans could or would try such a thing as infiltration. Our previous tactics may have given them some fuel for that line of thinking. By daylight Valletri was surrounded on three sides. General Walker the next morning established his forward command post under a railroad overpass. There was some protection from German artillery there but snipers became bothersome, so much so that the next morning an hour or more before daylight the usually mild mannered Ohio general got mad. He roused his sleeping staff from their blankets and bedrolls, and organized a sniper hunt with himself at the head of the column. But the hunt brought no results, although there was respite from any more of the Nazi varmints.

THE CORPS COMMANDER As Velletri fell that sunny late afternoon and there was only a scattering of shot, Lt. Gen. Lucien B. Truscott drove up in his jeep to where General Walker was standing at the edge of the town. "You can go in now, General," Walker said to Truscott, the Corps commander. "The town is yours." Truscott complimented him on the operation, gave credit where it was due. General Walker's job for that day was done. He was ready to return to his forward CP and plan the next day's run toward Rome. The Germans were retreating in full force, leaving delaying forces behind to cover their race for better protection north of the Tiber River. We piled into his jeep and the driver decided to return to the CP by a shorter route. The general was living with luck that day. We learned later that engineers stopped the jeeps following us. The road was heavily planted with mines. Our wheel tracks, they said, were over one of them. And just to show how badly fooled the Germans were, we learned from prisoners that outposts had reported two companies of Americans up in the Alban Hills. They had sent a battalion up there to wipe them out. The battalion ran into one of our regiments. You can imagine what happened then.

|