By Chris Paulos, museum volunteer

In Austin, Texas, a fearsome snake waits for you to walk within striking distance. It’s not a common Texas rattlesnake. This snake is an AH-1S Cobra helicopter gunship, and it waits for visitors to come face to face on a visit to the Texas Military Forces Museum at Camp Mabry in Austin.

The story of the revolutionary Cobra helicopter gunship is one of rapid innovation fueled by the dramatic needs of US military forces on the battlefield.

In the years following the Second World War, little thought was given to the idea of the helicopter as an offensive weapon. The Korean War (1950-1953) saw early helicopters used in the roles of medical evacuation and search-and-rescue. At the same time, the newly established Air Force jealously guarded its role as the primary aviation service. The Air Force focused squarely on the nuclear strike mission rather than the support of ground forces.

One of the earliest advocates for the offensive use of helicopters was Major General James Gavin, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division during World War II. His 1954 article “Cavalry, and I Don’t Mean Horses” sharply criticized the poor mobility of U.S. cavalry during the Korean War. Gavin blamed the increasing preeminence of heavily armored vehicles and the resulting dependence on roads for the failure to effectively delay the initial North Korean advance while the U.S. Army built up its forces as well as the failure to detect the Chinese attack in the fall of that year.

In 1955, Brigadier General Carl I. Hutton, then Commandant of the U.S. Army Aviation School, proposed a new type of combat organization centered on aircraft. Different aircraft would be developed to fill the roles of reconnaissance, strike, and air transport. Early experiments with armed helicopters were carried out by the aviation school through 1957.

The year 1962 was pivotal in the development of the helicopter gunship. That year the Bell Company, in Fort Worth, Texas unveiled a mockup of a proof-of-concept gunship helicopter. The D225 Iroquois Warrior used the engine and other mechanical components from the UH-1C. This model established the familiar layout of the gunship with pilot and copilot/gunner in tandem seats, a nose turret, and stub wings to carry rockets. The Army was impressed enough to request a second, flying demonstrator that flew the following year, named the Bell 207.

Also in 1962, the Army’s Howze Board recommended the creation of five “Air Assault” divisions, each with enough helicopters to carry a third of third of its infantrymen at one time. There would also be thirty-six helicopters armed with rockets. The 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) was organized and sent to Vietnam in 1965.

The Army’s long-term hopes were on the Lockheed AH-56 Cheyenne, the first prototype of which flew in September 1967. Unfortunately, the Cheyenne was not expected to be available until 1970, and the Army needed a dedicated gunship immediately.

Mark Folse, an engineer at Bell, found the solution. In order to introduce a new helicopter into the Army fleet there had to be a formal competition between manufacturers after a lengthy design process. Adding a new variant of an existing helicopter took less time and a lot less paperwork.

Bell already had a helicopter on hand to start with: the UH-1 Iroquois, more commonly known as the Huey. Folse’s team took the Lycoming T53 engine, transmission, tail rotor, and a host of other parts from the Huey and mated them to a new sleek fuselage. The resulting Model 209 aircraft took to the air in September 1965. In only two years time the production model was flying over battlefields in Vietnam.

The AH-1G Cobra saw its first combat action on September 4, 1967 – as part of a familiarization flight for General George Seneff, Commanding General of the 1st Aviation Brigade. What had been intended as a routine, non-combat flight turned into a baptism of fire when Seneff and Chief Warrant Officer John Thomson encountered a suspected Viet Cong sampan on the Mekong River. The sampan was sunk with rockets and machine gun fire. Regular operations began in October conducted by the 334th Assault Helicopter Company.

Attack helicopters changed the battlefield narrative for soldiers fighting on the ground. Soldiers now had air support which belonged to them the same way as artillery did. Calling in Air Force fighter-bombers required a lengthy process in which the request had to be moved through liaison officers to the other branch then moved up its chain of command for approval. However, the Cobra gunships could directly support ground units. If mortars were the infantryman’s “pocket artillery,” then the Cobra was his pocket air force.

An attack helicopter’s low speed, though a vulnerability, is also one of its greatest assets. A jet fighter would approach the battlefield at hundreds of miles per hour. Give the pilot a target at a distance of 10 miles and he has less than ninety seconds to confirm the target’s identity, maneuver into position for the attack, and make any other final adjustments to onboard systems. By way of contrast, the helicopter’s ability to fly at low speeds and hover allows it to loiter around an engagement area and observe the battle over time.

The technology, cutting edge at the time, was formidable, but the Cobra was designed to work with other units in tandem. Teamwork was required, and the Army was ready to use the Cobra in partnership with other assets to change the battlefield balance of power.

In Vietnam, each air cavalry troop was divided into three platoons which complemented one another’s capabilities. The Aero Scout Platoon flew scout helicopters, first the OH-23, later the OH-6. This platoon was the primary reconnaissance element. The Aero Rifle Platoon provided a ground combat capability with transport helicopters and four infantry squads. Supporting both was the Aero Weapons Platoon with gunship helicopters, first armed Hueys, then Cobras.

The scouts and gunships normally worked as mixed pairs. The scout helicopter would take the lead to attract enemy fire. The Cobra would then dish out its venom against the enemy targets.

Two hundred seventy-nine Cobras were lost on the battlefields of Vietnam. The worst years were 1969 and 1970, which together saw over half of the total loss. On the battlefield, the young Cobra helicopter pilots often faced anti-aircraft guns, machine guns, and small arms. Even a rifle round could cause serious damage if it hit any of the exposed moving parts which made up the rotor assembly. Towards the end of the war a new threat emerged, that of the man-portable surface-to-air missile.

“We had no defense against SA-7s,” Cobra pilot Carl “Skip” Bell recalled in a 2017 interview. “The only thing we could do is fly…hugging the ground, if we knew an area had SA-7s.” Later models of the Cobra would be equipped with countermeasures against infrared homing missiles.

The Cobra helicopter on display at Camp Mabry in Austin, Texas has the serial number 68-15153. This aircraft is one of 290 converted in the late 1970s from the original AH-1G model to the AH-1S configuration. It served with Troop D, 124th Cavalry Regiment before retiring to the museum in 1995.

The 124th, stationed in Austin, was the Texas 49th Armored Division’s main reconnaissance unit. In that role it operated 12 Cobras in addition to scout helicopters and ground vehicles. The 49th also contained the 1st Battalion, 149th Aviation Regiment at Houston which operated 21 Cobras. Both of these units operated the AH-1 between 1985 and 1996.

The 49th was one of six Army National Guard divisions to have heightened priority for new equipment and, in the event of war, required to quickly deploy to Europe and reinforce the NATO forces stationed in Germany.

In Europe, AH-1 pilots faced a formidable array of short-range anti-aircraft weapons ranging from small man-portable missiles found in every battalion to the “Osa” vehicle-launched missile with a range of over 10 kilometers. But the most dangerous threat was the old fashioned gun in the form of the ZSU-23-4 “Shilka.” Mounted on a light tank chassis, this weapon boasted four 23 millimeter guns with a radar for automatic target tracking. The Shilka could respond faster than missiles to the appearance of a new target. Unlike infrared homing missiles of the time, it could shoot at a Cobra from any angle.

The primary mission was no longer support for counterinsurgency but rather the destruction of massed Soviet tank forces. To accomplish this and other missions, Cobra pilots had access to a variety of weaponry suited for a variety of targets and situations. The pilot, who is also the commander of the aircraft, sits in the rear cockpit. The co-pilot/gunner sits in front. Either one of them can fly the aircraft.

The M28 turret located in the chin position contains two M134 electrically-powered six-barrel rotary machine guns. The turret is modular and can also carry two M129 automatic grenade launchers or one of each weapon. Usually known as the “minigun,” the M134 could fire at either 2,000 or 4,000 rounds per minute. The grenade launcher could fire 400 rounds per minute. The gun turret could be aimed by the pilot with a fixed reflex sight, by either crewman using the M65 Telescopic Sight Unit (TSU), or by the gunner using a revolutionary helmet-mounted sight (HMS).

The HMS consisted of a headset with an eyepiece and a mechanical linkage which measured the direction in which the gunner’s head was pointed. The gun turret automatically turned so as to always point in the same direction. The eyepiece contained the crosshairs for aiming.

The minigun and grenade launcher were versatile weapons but their short effective range, only 1,000 meters for the Minigun, often made using them dangerous in combat since pilots had to bring their aircraft within the range of enemy rifles and machine guns. Other weapons were needed to reach further and destroy harder targets.

Above the turret, occupying the very nose of the aircraft, is the Telescopic Sight Unit. The TSU is the most important and most visible part of the upgrade from the original AH-1G. It is a sophisticated optical device offering the gunner a 2x or 13x magnification view of a target. The gunner points the TSU with a small joystick in the front cockpit. While the TSU could be used to aim the gun turret, its primarily role was to guide the BGM-71 TOW anti-tank missile. A quadruple missile launcher can be seen at the end of each wing.

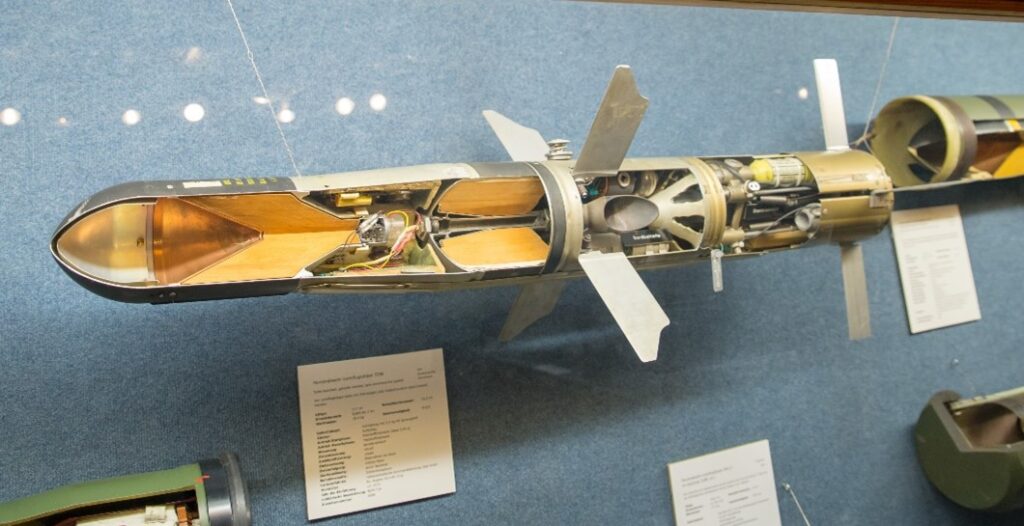

The TOW, which is short for “Tube-launched, Optically-tracked, Wire-guided,” is an example of a command-guided missile. This means the missile itself has no homing seeker, no brain of its own. It is entirely dependent on instructions from the launcher. In this case those instructions are passed through a pair of wires. Other missiles, such as the Russian “Kokon,” receive commands by radio.

To fire a TOW, the gunner first aims the Telescopic Sight Unit so that the crosshairs are over the target. The pilot now has to steer the aircraft to within certain parameters. After the missile is fired, the electronics on the aircraft measure the difference between the direction the missile is flying and the direction to which the sight is pointed. To do this a sensor in the TSU tracks an infrared beacon located at the back of the missile. Whenever the missile is off course, steering directions are sent through the wires to correct it. As long as the pilot keeps his crosshairs on the target the missile should hit.

The TOW was first used in combat in Vietnam on May 2, 1972. The missiles were launched from modified UH-1B transport helicopters. Cobras from the 361st Assault Helicopter Company escorted the lumbering Hueys while they destroyed four tanks and an artillery piece.

Wire guidance allows all the expensive electronics to be on the multi-use aircraft rather than the single-use missile. It also results in a system which is extremely difficult to jam. However, there are also some drawbacks. TOWs fired over salt water or power lines can short-circuit. The range of the missile is limited by the amount of wire that can be fit into the missile. The greatest drawback, as far as the aircrew’s survival is concerned, is the necessity to have the target in crosshairs for the entire flight time of up to 23 seconds.

The TOW was a late arrival to the Cobra’s arsenal. Moving to the inner wing pylons we can see the most powerful weapon available to the pilots fighting in Vietnam. The “Hydra” family of unguided rockets was derived from the Mark 4 air-to-air rockets used by Air Force interceptors such as the F-86D.

Our aircraft carries two rocket pods each carrying seven rockets. The Cobra could also be equipped with larger pods carrying nineteen rockets each. Rockets were fired by the pilot using his reflex sight. Like the Mark 4, the Hydra rockets spread out after launch, and therefore a salvo was required to ensure target destruction. While not precise, they were perfect for delivering the maximum amount of high explosive in the shortest amount of time over the widest possible area.

The Cobra continued to be upgraded throughout the Seventies and early Eighties. The AH-1S “Step Two” replaced the existing minigun/grenade launcher turret with a new model featuring the M197 cannon, a three-barrel rotary weapon which fired a 20 mm round. The new gun delivered not only greater firepower but greater range so that using the gun was less hazardous for the crew. The “Step Three” upgrade added a heads-up display, ballistics computer, and laser rangefinder.

Yet, by the 1980s, the Army Cobra was showing its age. The single engine restricted the payload that could be carried, especially in high-temperature conditions when the rotors could produce less lift. The Cobra lacked the range to be effective at interdiction missions behind the front lines, a task which was emphasized by the contemporary AirLand Battle doctrine. The Cobra also had little ability to fight at night. Only some of the newest AH-1s were equipped with a thermal imaging sight for the TOW missile.

The Cobra fought in the Gulf War (1991) alongside its replacement the AH-64 Apache. The last AH-1s in active duty service were withdrawn in 1999. Some National Guard battalions kept their Cobras for another two years with final retirement in 2001. Twin-engine Cobras continue to serve in the Marine Corps with the latest AH-1Z version currently in production.

The Cobra helicopter gunship at the Texas Military Forces Museum on Camp Mabry recently underwent a restoration project, and is now waiting to show its fangs again for visitors.